In August I went with two Suffolk Jaguar friends from Thames Valley and Kent to a special show in Surrey, organised by a local property developer in aid of Help the Heroes. Held in the grounds of his farmhouse, about 800-1,000 cars turned up including some very rare machines. Robert Lewis has his own collection of about 35 cars, all beautifully restored and painted, including an SS1 Airline, an SS1 drophead, an SS100, an SS 2.5 litre, an XK120, some MGs and several Edwardian cars.

Midway through the morning we heard an announcement that there would be a 20-minute talk in the garage housing his vintage cars. We didn’t hear what the subject was, but went there anyway. Having made our way through the crowd to reach it, the speaker stood up and announced he was going to talk about petrol. Our spirits sank, as it didn’t sound very enticing and we’d be stuck there for at least 45 minutes.

How wrong we were! He was a good speaker and made his hobby, the history of petrol distribution and pumps, absolutely fascinating. I would like to thank Alan Chandler, and provide a link to his website: http://www.petroliana.co.uk/. I cannot do justice to him, but the following represents just some of what he said.

How wrong we were! He was a good speaker and made his hobby, the history of petrol distribution and pumps, absolutely fascinating. I would like to thank Alan Chandler, and provide a link to his website: http://www.petroliana.co.uk/. I cannot do justice to him, but the following represents just some of what he said.

The first steam-powered, self-propelled vehicles were difficult to operate. Their boilers required at least an hour or more firing by a stoker (‘chauffeur’ in French) to create enough steam to start. The 1865 Locomotive Act, known as the ‘Red Flag Act’, also imposed a speed limit of 4mph (2mph in town) and demanded a crew of three with an additional person walking at least 60 yards in front with a red flag to warn others and help with horses.

The internal combustion engine was much lighter and more convenient, making personal transport by car a real possibility. However, largely because of the above legislation, its development in Britain lagged behind that of Europe and America. Cars were expensive and, in its earliest days, motoring in Britain was the preserve of the wealthy few, not helped by the sometimes arrogant attitude of rich motorists causing additional resentment.

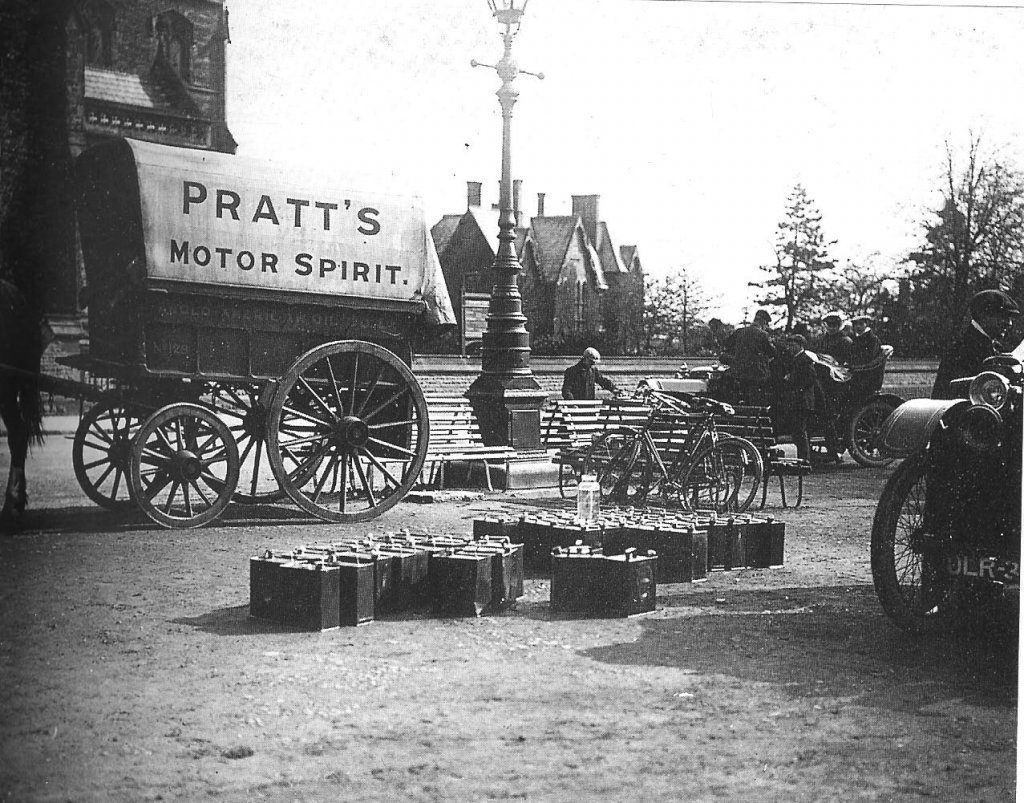

Fuel, then known as motor spirit (‘petrol’ was a trade name used by Carless Capel & Leonard), was distributed by rail and horse-drawn tankers, then pumped by hand into barrels. It was sold from chemist shops, or purchased and delivered to the owner’s home, in 2-gallon cans. Only a limited quantity could be carried or stored – its explosive potential was understood – and a deposit of 2/6d (eventually rising to 9/-) was paid on each can. There were more than 200 different distributors but no filling stations and many roads, especially outside towns, were unmetalled. So, up till the First World War, long-distance journeys represented quite a challenge.

Fuel, then known as motor spirit (‘petrol’ was a trade name used by Carless Capel & Leonard), was distributed by rail and horse-drawn tankers, then pumped by hand into barrels. It was sold from chemist shops, or purchased and delivered to the owner’s home, in 2-gallon cans. Only a limited quantity could be carried or stored – its explosive potential was understood – and a deposit of 2/6d (eventually rising to 9/-) was paid on each can. There were more than 200 different distributors but no filling stations and many roads, especially outside towns, were unmetalled. So, up till the First World War, long-distance journeys represented quite a challenge.

However, as motor cars and their use became more popular so the demand for fuel increased. Chemists, blacksmiths and general stores began selling petrol on the roadside, pumping it from barrels on carts (‘chariot pumps’), or via free-standing pumps or wall-hung pumps, into 2-gallon cans which were then tipped into the car with a funnel. The first public pump selling motor spirit is thought to have been at Brooklands Circuit in 1908.

However, as motor cars and their use became more popular so the demand for fuel increased. Chemists, blacksmiths and general stores began selling petrol on the roadside, pumping it from barrels on carts (‘chariot pumps’), or via free-standing pumps or wall-hung pumps, into 2-gallon cans which were then tipped into the car with a funnel. The first public pump selling motor spirit is thought to have been at Brooklands Circuit in 1908.

Almost all such ‘skeleton’ pumps were imported from S.F. Bowser or Gilbert & Barker in America, as there were no English makers. Australians still use the term bowser.

Almost all such ‘skeleton’ pumps were imported from S.F. Bowser or Gilbert & Barker in America, as there were no English makers. Australians still use the term bowser.

One advantage of this system for early motorists, who understood the variation between brands and were suspicious of unscrupulous vendors, was that they could easily see the quantity they were paying for, use a filter with the funnel for particles and see the fuel (to check it really was petrol) as it was being poured into the car.

As demand and the quantities of fuel rose and the fire risks increased, so did the need for underground storage tanks and more sophisticated ‘skeleton’ pumps. However, motorists were suspicious of these: how could they be sure they were getting the right amount of uncontaminated fuel? The favoured solution was to pump the fuel up, two gallons at a time, into glass cylinders where it could be inspected and then fed by gravity through a hose into the vehicle’s tank.

To make the pumps more visible to passing motorists and attract custom, the pumps often carried a beacon light, the equivalent of today’s huge neon sign at the entrance to a petrol station. They also developed stylistically; French-made pumps were quite impressive and Art Deco designs became popular in the late 1920’s and 1930’s.

To make the pumps more visible to passing motorists and attract custom, the pumps often carried a beacon light, the equivalent of today’s huge neon sign at the entrance to a petrol station. They also developed stylistically; French-made pumps were quite impressive and Art Deco designs became popular in the late 1920’s and 1930’s.

Excavating an underground tank and purchasing the equipment was expensive. Shell was the first to come up with the idea of doing this for a discounted price, repayable in instalments, in exchange for a commitment to sell only their brand of fuel – the first ‘tied’ garages.

The first purpose-built filling station was opened by the AA – an organisation originally founded by motorists to warn each other of police speed traps ahead – at Aldermaston near Reading in 1919. As the number of cars on the road expanded dramatically, with the launch of the Austin 7 in 1922, and Ford’s expansion at Dagenham and launch of the Morris Minor in 1928, so too did the number of petrol pumps.

The first purpose-built filling station was opened by the AA – an organisation originally founded by motorists to warn each other of police speed traps ahead – at Aldermaston near Reading in 1919. As the number of cars on the road expanded dramatically, with the launch of the Austin 7 in 1922, and Ford’s expansion at Dagenham and launch of the Morris Minor in 1928, so too did the number of petrol pumps.  They also developed technically as the need grew to dispense larger quantities more quickly. Five-gallon glass cylinder pumps became more popular. When metering pumps came into use, a small glass globe with a turbine inside replaced the measuring cylinder, but assured the customer that gasoline really was flowing into the tank.

They also developed technically as the need grew to dispense larger quantities more quickly. Five-gallon glass cylinder pumps became more popular. When metering pumps came into use, a small glass globe with a turbine inside replaced the measuring cylinder, but assured the customer that gasoline really was flowing into the tank.

Brands such as Pratts, Shell, BP and Esso and others became larger and more dominant, with more ‘tied’ arrangements. The popularity of pumps which could dispense three or four different brands of fuel diminished. The first electric pumps appeared at the end of the 1920’s and began to be seen in the newer filling stations and roadside garages in the 1930’s, slowly replacing earlier pumps throughout the 1940’s and 1950’s.

Alan Chandler says that his personal interest is in the early history, up to the 1940’s. However I’m sure that the history of petrol stations since the second world war could be equally interesting.

Richard Gibby