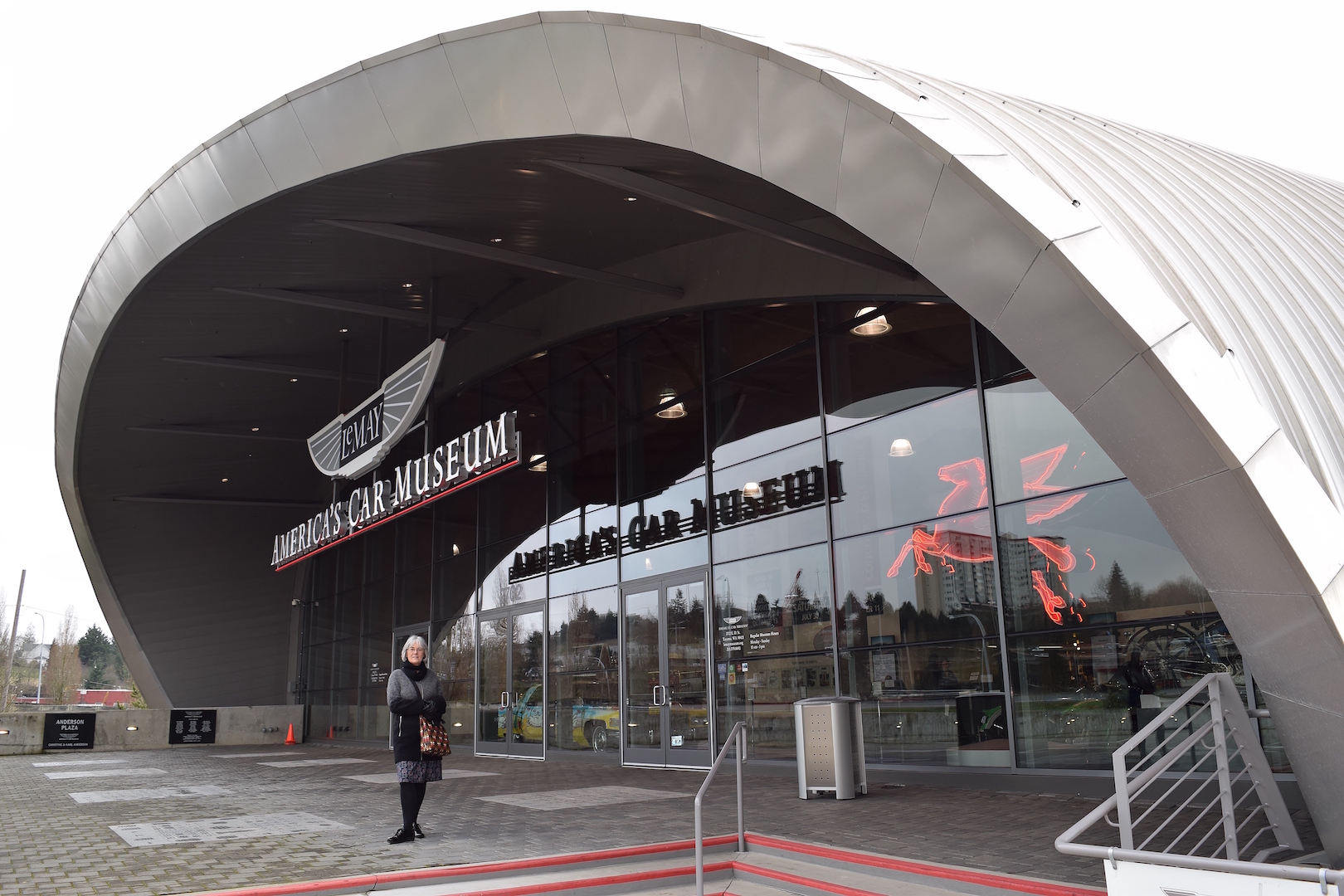

Since the publication of the first part of my article on this inspiring venue in April, I have received a deluge of requests from two members asking when the next instalment of the museum trip would be published. Wait no longer, because here it comes. But, before we begin, let me first extend a warm welcome and a hearty “G’day” to our readers in Brisbane and Melbourne…it was a great pleasure to meet up with you folks again. And, lest we forget, “Hello” to a very special person in Seattle.

Those with good memories will recall that I signed off just as we were about to venture along the ramp down to Lucky’s Garage on Level 3. We would take in some of the stunning displays on the way down for this is the Custom Coachworks Ramp, so named after the sparkling exhibits which reside along its length. This display of the best automobiles of mostly the inter-war years would have any sensible petrolhead salivating and is one of my favourite zones. So, what is it all about? Well, basically, heritage.

American coach-building heritage

Early cars were known as “horseless carriages” and they looked it, being built by horse-drawn wagon/carriage companies that pioneered the West. They were owned by the lucky few. When mass production brought down prices, thereby increasing availability to ordinary working people, owning a car was no longer sufficient to set any self-respecting entrepreneur, businessman, socialite or movie star apart from the masses. Sensing the opportunity, many of the remaining traditional manufacturers turned their coach-building skills to create custom bodies on chassis supplied by the car manufacturers which both satisfied the needs of the rich clientele and started the “golden age” of handcrafted automobile coachwork. Space is sadly lacking to detail all such coach builders here, but I will take a stab at a few that might ring some bells.

Back in 1917 the Lincoln Motor Company was founded by an uncle of Walter M Murphy, who duly awarded the California franchise to his nephew. Walter set about dressing the Lincolns in handmade coach-built bodies and sought the help of George R Fredricks, a renowned coach-builder, whom he moved to Pasadena in California to build specialist bodies not only for Lincoln, but also for top-drawer marques including Packard, Rolls Royce and Duesenberg, particularly the iconic Duesenberg Model J. Celebrities of the day – Rudolf Valentino, Buster Keaton et al – soon had them filling their garages.

Back in 1917 the Lincoln Motor Company was founded by an uncle of Walter M Murphy, who duly awarded the California franchise to his nephew. Walter set about dressing the Lincolns in handmade coach-built bodies and sought the help of George R Fredricks, a renowned coach-builder, whom he moved to Pasadena in California to build specialist bodies not only for Lincoln, but also for top-drawer marques including Packard, Rolls Royce and Duesenberg, particularly the iconic Duesenberg Model J. Celebrities of the day – Rudolf Valentino, Buster Keaton et al – soon had them filling their garages.

The Brewster Company could trace its origins even further back to the early 1800s, but it was in 1910 that it built its automotive coachworks, catering for the high end of the market. Families including the Rockefellers, Vanderbilts and Astors were regular clients. Its bodies could be found on American-built Rolls Royces, and, in 1924, Rolls Royce of America bought the company. I believe that Rolls Royce was the first foreign car maker to set up production facilities in the United States, in 1919 in Springfield, Massachusetts. It still remains the only place outside England where they have been built. Sadly, the great Depression, high costs and marketing blunders put paid to both Rolls Royce USA and Brewster by 1937.

Leaving Brewster in 1920, draftsmen Tom Hibbard and Ray Dietrich formed Le Baron Carrossiers. The Le Baron name was chosen from a list of French words that they thought would sound classy over the phone! Well, it must have worked for a New York State Lincoln dealer hired them to design a sporty body for the old fashioned 1920 Lincoln he was selling. It was a sales success and they went on to design bodies for Packard, Cadillac, Duesenberg, Lincoln and Chrysler, the latter still using the Le Baron moniker. Look for aerodynamic designs and a signature “sweep” of the body panelling to pick out their work.

The lucky owners were many and varied but they all had one thing in common…money. You needed lots of it to procure one of these dream machines. Let’s take a look at a few as we pass down the automotive line up.

Custom Coachworks Ramp

Representing American “royalty”, and probably the richest of all, was John D. Rockefeller who made his fortune by refining oil and founding Standard Oil, better known in the UK as Esso for obvious reasons. He was also a great philanthropist and died in 1937 at the ripe old age of 97.

Having captured the great man’s life story in four lines, I can now go on to say that, until 1905, it appears that he was anti-car, plastering his estate with signs stating “No motor cars allowed”. A little ironic, really, considering the industry that he helped build, but we all know that Americans don’t do irony! Nevertheless, he must have experienced a change of heart because, after that date, it was reported in the press that he had taken a great interest in “automobiling” and would learn to run a machine himself. The family acquired many coach-built automobiles over time, including two Simplex Crane model 5’s (circa 1918) fitted with Brewster bodies – one an open top for the summer, the other a closed vehicle for the winter. Presumably, they hadn’t invented convertibles then.

Coach-built cars were also a magnet to Hollywood stars. Gary Cooper bought the only Duesenberg SSJ made at that time. Having seen this 125mph, short wheelbase model fitted with a 400hp supercharged engine with ram horn intakes, his friend, Clark Gable, decided he must have one too. So the factory made another one, hence doubling the total production run to two! As is often the case today, the factory never actually sold it to Gable, merely loaning it to him free of charge thus benefiting from the publicity which ensued. As a footnote, Gable took delivery of an early XK120, and one or two more after that, which helped Jaguar’s profile in the USA. Check out MDU 420, which I believe was one of his.

It wasn’t just stars of the thirties that these cars were sold to. One of the highest paid actors of the silent era was Tom Mix (did he play cowboys?) who had a collection to match his status. He owned a Duesenberg Convertible, clad in coachwork by Brokaw Auto, which brandished cow horns from the radiator. His friend, Harley Earl – more on him later – designed him a car with a leather saddle on the roof! Sadly, not on display here.

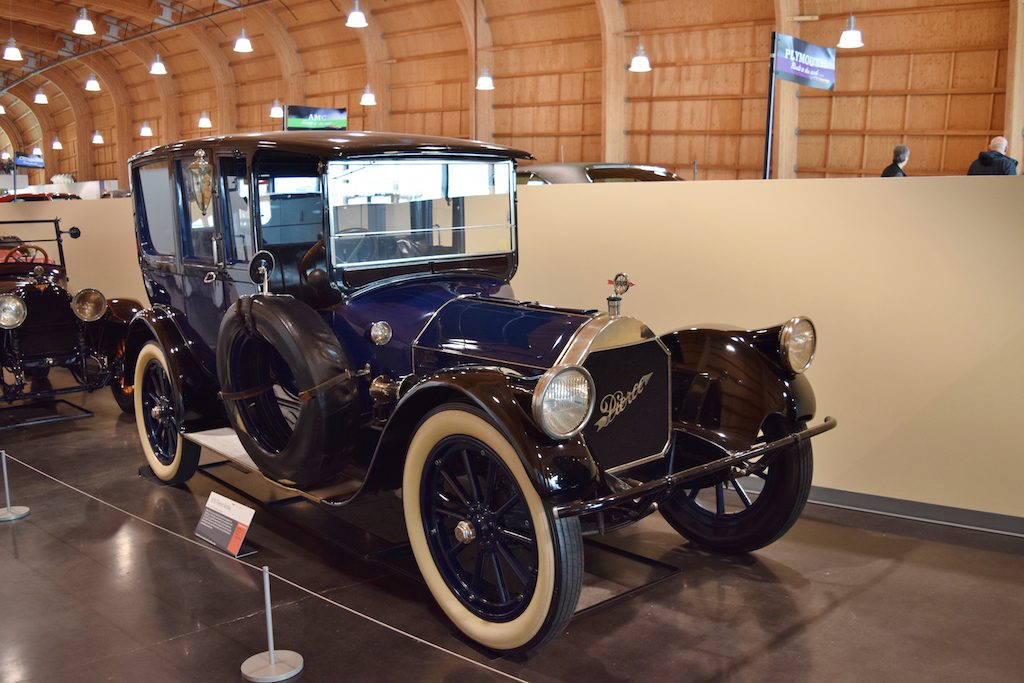

One of his contemporaries, equally highly paid, was Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, an actor, comedian, screenwriter and director who started his career in 1913. He mentored Charlie Chaplin, discovered Buster Keaton and Bob Hope and was offered a $1 million contract by Paramount, a staggering amount for 1920. Yet, he is little remembered today. This is most likely due to the scandal surrounding the death of a young actress at one of his parties. He was accused of raping and accidentally killing her – serious stuff – and convicted on, some may say, flimsy evidence. Between 1921 and 1922, he was tried twice before finally being acquitted with a formal apology after his third trial. With his films banned and publicly ostracised, he worked occasionally as a film director until he was able to return to acting. Finally, on the same day that Warner Bros signed him up for a full feature film, he died of a heart attack at only 45 years old. Very sad. But, he did own an imposing Pierce Arrow PA 38-C Brougham. It featured a hidden cabinet for Prohibition-era liquor and it was only driven in fine weather, since it had no windscreen wipers! In today’s money it would cost $300,000. There is a blue 1916 example on display here. It is significant since it is a “Nickel Period” car which, as the name suggests, had all its brightwork made from nickel, unlike the earlier brass-adorned vehicles and the later “Chrome Period” cars. Not many “Nickels” however, have survived.

One of his contemporaries, equally highly paid, was Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, an actor, comedian, screenwriter and director who started his career in 1913. He mentored Charlie Chaplin, discovered Buster Keaton and Bob Hope and was offered a $1 million contract by Paramount, a staggering amount for 1920. Yet, he is little remembered today. This is most likely due to the scandal surrounding the death of a young actress at one of his parties. He was accused of raping and accidentally killing her – serious stuff – and convicted on, some may say, flimsy evidence. Between 1921 and 1922, he was tried twice before finally being acquitted with a formal apology after his third trial. With his films banned and publicly ostracised, he worked occasionally as a film director until he was able to return to acting. Finally, on the same day that Warner Bros signed him up for a full feature film, he died of a heart attack at only 45 years old. Very sad. But, he did own an imposing Pierce Arrow PA 38-C Brougham. It featured a hidden cabinet for Prohibition-era liquor and it was only driven in fine weather, since it had no windscreen wipers! In today’s money it would cost $300,000. There is a blue 1916 example on display here. It is significant since it is a “Nickel Period” car which, as the name suggests, had all its brightwork made from nickel, unlike the earlier brass-adorned vehicles and the later “Chrome Period” cars. Not many “Nickels” however, have survived.

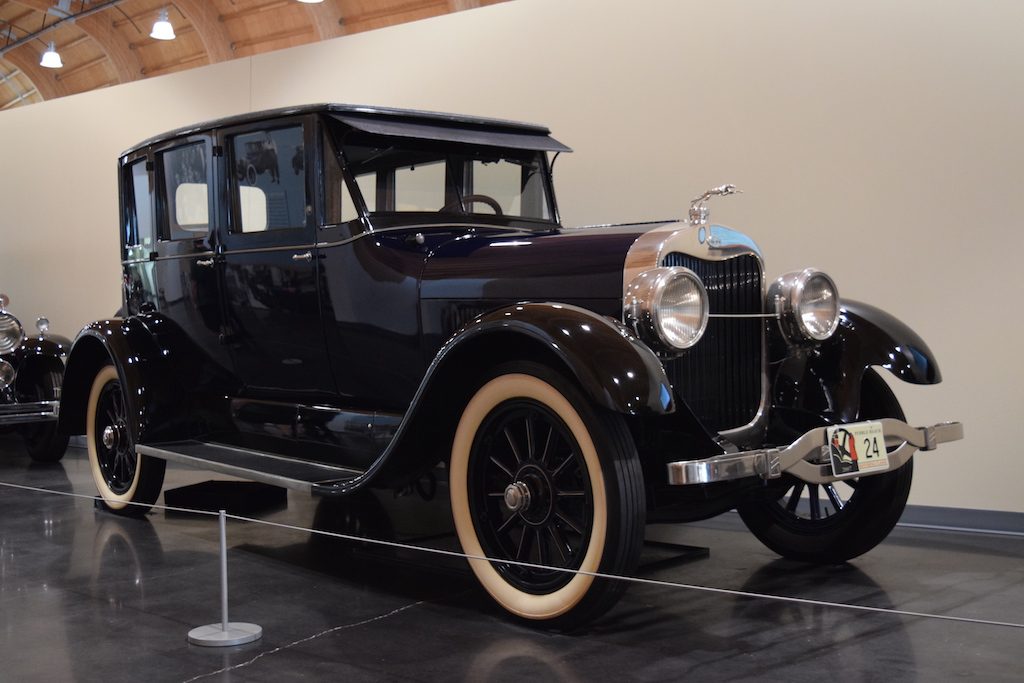

Strolling further along, we pass the Simplex, a Rolls Royce 20/25 Silver Ghost town car bodied by Willoughby, a 1924 Lincoln Model L, also a town car, with coachwork by Judkins (this car completed the Pebble Beach 1500 mile Motoring Classic in 2006) and a 1929 Cadillac Series 341B Victoria Coupe.

Strolling further along, we pass the Simplex, a Rolls Royce 20/25 Silver Ghost town car bodied by Willoughby, a 1924 Lincoln Model L, also a town car, with coachwork by Judkins (this car completed the Pebble Beach 1500 mile Motoring Classic in 2006) and a 1929 Cadillac Series 341B Victoria Coupe.

Incidentally, 1929 was Caddy’s most successful year to date and the Series 341B sported new innovations such as safety glass and an all-synchromesh transmission. The latter was as revolutionary as their 1912 self-starter, making driving that much easier and relaxing.

Incidentally, 1929 was Caddy’s most successful year to date and the Series 341B sported new innovations such as safety glass and an all-synchromesh transmission. The latter was as revolutionary as their 1912 self-starter, making driving that much easier and relaxing.

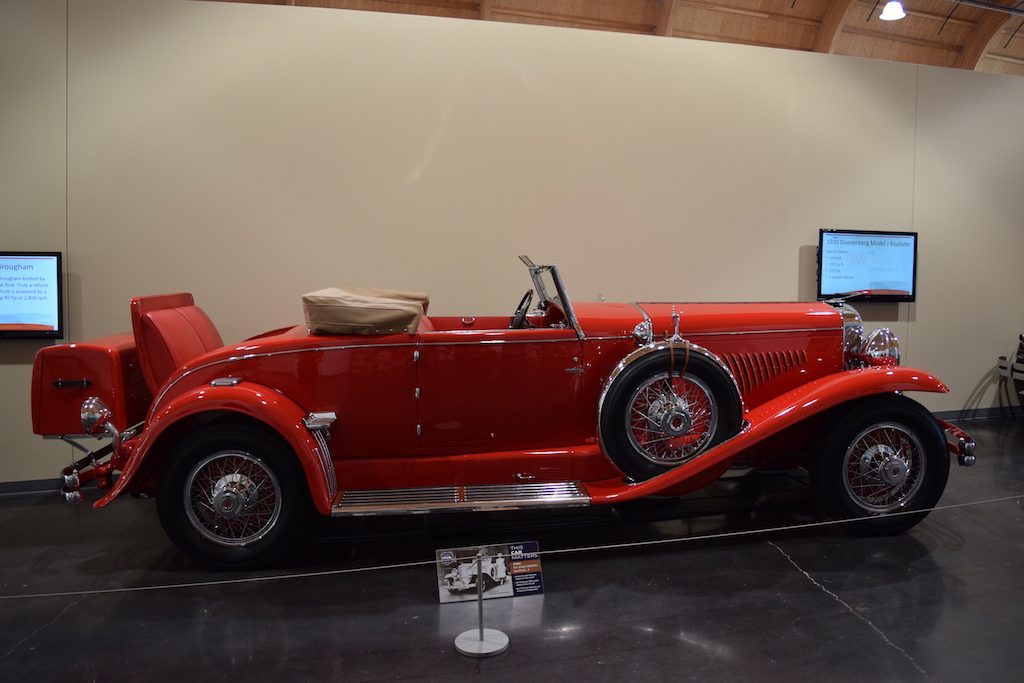

Don’t miss the bright red 1930 Duesenberg Model Y roadster: 265hp, straight eight, DOHC, manual three-speed, capable of hitting 120mph – sublime! A little further along, we see another ‘Duesy’, this time a Model J convertible sedan which starred alongside Bruce Willis and James Garner in the film “Sunset”. It boasted a 6900cc 32-valve straight eight engine, designed by Fred Duesenberg and built by Lycoming, producing similar outputs as the roadster.

Don’t miss the bright red 1930 Duesenberg Model Y roadster: 265hp, straight eight, DOHC, manual three-speed, capable of hitting 120mph – sublime! A little further along, we see another ‘Duesy’, this time a Model J convertible sedan which starred alongside Bruce Willis and James Garner in the film “Sunset”. It boasted a 6900cc 32-valve straight eight engine, designed by Fred Duesenberg and built by Lycoming, producing similar outputs as the roadster.

Both Duesenbergs are to die for, so who was behind these beautiful machines?

Errett Cord, a former racing car driver,

mechanic, successful businessman and,

moreover, a talented salesman was the person

responsible for the Model J. He initially

became involved with the Auburn Automobile

Company, turning around its poor

performance and eventually becoming its

president. Whilst in this role, he bought the

Duesenberg Company in 1926 and capitalised

on its reputation of building successful racers

with models such as the J. Poor Fred died in

1932 as a result of rolling his car at high speed

, becoming the first person to die as a result of

an accident in a car bearing the owner’s name.

Both Duesenbergs are to die for, so who was behind these beautiful machines?

Errett Cord, a former racing car driver,

mechanic, successful businessman and,

moreover, a talented salesman was the person

responsible for the Model J. He initially

became involved with the Auburn Automobile

Company, turning around its poor

performance and eventually becoming its

president. Whilst in this role, he bought the

Duesenberg Company in 1926 and capitalised

on its reputation of building successful racers

with models such as the J. Poor Fred died in

1932 as a result of rolling his car at high speed

, becoming the first person to die as a result of

an accident in a car bearing the owner’s name.

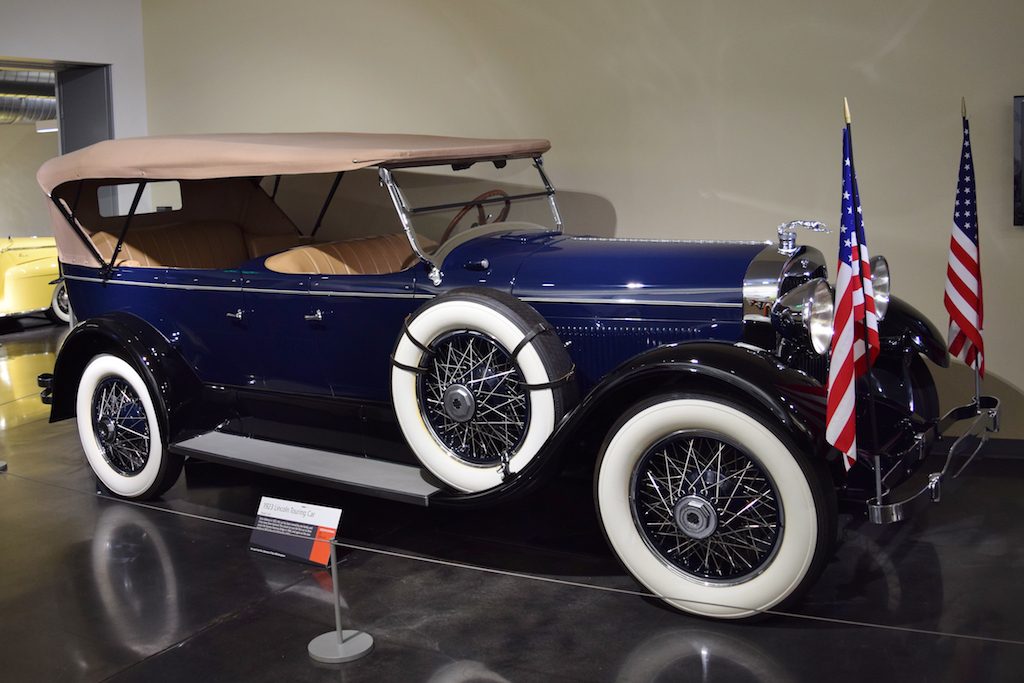

Finally, behind a magnificent 1920 Buick

Abadal, stands the last, but

far from least, car on the ramp: a 1923 V8 Lincoln 124A

touring car with an interesting history to

accompany it.

Finally, behind a magnificent 1920 Buick

Abadal, stands the last, but

far from least, car on the ramp: a 1923 V8 Lincoln 124A

touring car with an interesting history to

accompany it.

Since delivery in 1923, this car has been owned by one family and has never been licensed. As the story goes, the Titus family ran a Ford dealership in Washington State and took delivery of the Lincoln, Ford having recently bought the company. Unfortunately, it was too expensive for those used to buying Fords and they could not sell it, so they kept it. One of only 1,182 built, it was the first car to cross the Tacoma Narrows Bridge on its opening day in July 1940 (see the first part of my article). In July of 2007, the Lincoln once again made the inaugural crossing of the latest Tacoma Narrows Bridge which, thankfully, still stands today. The car has also carried Franklin Roosevelt and Queen Elizabeth II, amongst other notable dignitaries. As a footnote, I believe that the dealership still thrives in Tacoma, and in Washington State in general, as Titus-Wills.

Since delivery in 1923, this car has been owned by one family and has never been licensed. As the story goes, the Titus family ran a Ford dealership in Washington State and took delivery of the Lincoln, Ford having recently bought the company. Unfortunately, it was too expensive for those used to buying Fords and they could not sell it, so they kept it. One of only 1,182 built, it was the first car to cross the Tacoma Narrows Bridge on its opening day in July 1940 (see the first part of my article). In July of 2007, the Lincoln once again made the inaugural crossing of the latest Tacoma Narrows Bridge which, thankfully, still stands today. The car has also carried Franklin Roosevelt and Queen Elizabeth II, amongst other notable dignitaries. As a footnote, I believe that the dealership still thrives in Tacoma, and in Washington State in general, as Titus-Wills.

Harley Earl

Well, we are now at the bottom of the ramp and about to enter Lucky’s Garage, so maybe I will save that for another time. But I couldn’t leave before mentioning one of the most influential stylists of the first half of the twentieth century, Harley Earl. He started work in his father’s custom coachbuilding shop in Hollywood, catering to the movie stars of the time – see earlier. Later the shop was bought by Cadillac, whose General Manager, Lawrence P Fisher, asked Earl to design the 1927 La Salle. It was a success and impressed Alfred P Sloan, CEO of the mighty General Motors. Sloan hired Earl to create the Art and Colour Department at GM, thus establishing the first styling department at a production automobile manufacturer and moving design from the bespoke to the more available mass produced vehicles.

Earl was an innovator and introduced the practice of making full-scale clay models of the car bodies to refine the design before production, lending a more sculptural approach rather than the rectangular shaping seen on engineering-focussed designs. The practice still goes on today, despite CGI. With the completion of the Buick Y Job show car, he effectively originated the one-off show car used to gauge public reaction. We call them “concept cars” today. Wrap-around windscreens, two-tone paint and the ever increasingly flamboyant “tail fins” were some of his signature design themes. And for those of you (well one, really) lucky enough to own a Corvette, that was one of his initiatives also.

See you later.

Neil Shanley